How conserving the jaguar king can protect its forest kingdom

It’s no exaggeration to say that the jaguar is special.

It’s the biggest of the ‘big cats’ in the Americas. Its bone-crushing jaws are more powerful than even the lion or the tiger – the only two larger felines in the world. This stocky ambush-predator can be seen clawing up and down trees, roaming the rainforest and swamplands, and pouncing on prey with its hefty mass of up to 160 kg. Though in calmer moments, curled up with its cubs in a tree, it still purrs like any other cat.

Native to the Americas and ranging from northern Mexico to northern Argentina, the jaguar has been a symbol of power in human culture for centuries. Its name comes from yaguar, the Tupí-Guaraní word meaning ‘he who kills with one leap’. With a roar like thunder, the colour of fiery sun, and spots like the moon, one can see why the jaguar is revered as a king. But a king cannot rule by strength and fear alone; a king must also protect.

What makes the jaguar a protector of the forest?

Firstly, if a jaguar is present, it means there is also an abundance of prey species, and so the jaguar is an excellent indicator of a healthy forest ecosystem. The more jaguars, the larger and healthier the connected habitat.

It could also be said that when a jaguar kills its prey, it brings a whole forest to life. This is because the jaguar is considered a ‘keystone species’ due to their role as a top predator. If such a species is taken away from a habitat – like the top ‘keystone’ taken away from an arch – the whole ecosystem can change or even start to collapse. Bring the apex predator back, and piece by piece, species by species, the system will return to its natural balance. A great example of this in action is this incredible video by National Geographic that shows how Yellowstone National Park was transformed when wolves were reintroduced.

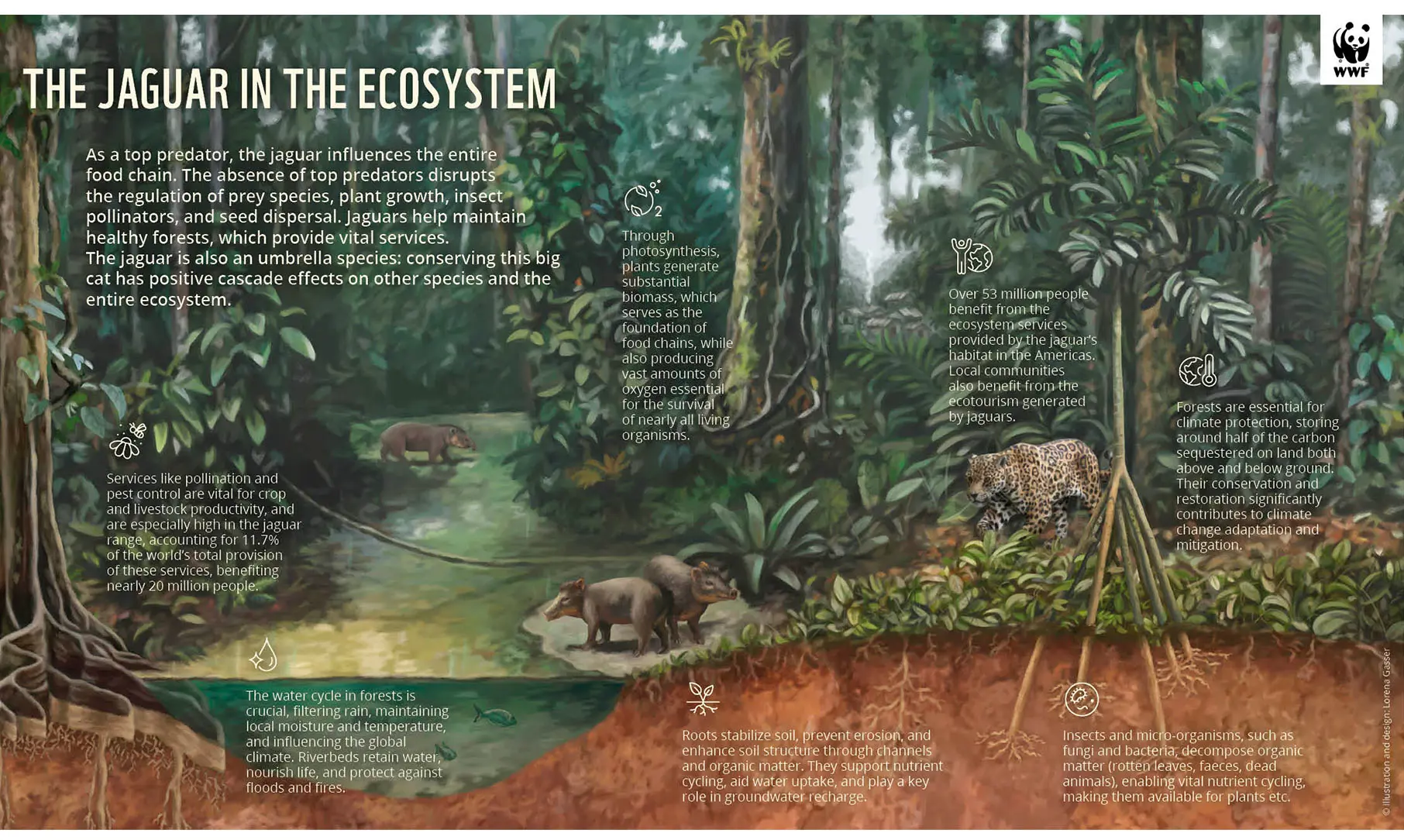

From the change in abundance of smaller predators such as ocelots, and plant-eating prey including white-tailed deer and collared peccary, down to the level of pollinating insects and plants whose roots stabilise soil – it’s a cascade that can affect the structure, diversity, and resilience of an entire landscape and end up affecting many species, including us humans. While more research specific to jaguars is needed, some scientists describe the process occurring in forests with a lack of top predators as an ‘ecological meltdown’.

But the good news is that when jaguars and their habitats are healthy, it benefits us all. Over 53 million people benefit from the environmental services –such as clean drinking water, carbon capture, oxygen production, pollination – provided by the forests that jaguars call home.

Restoring the jaguar’s kingdom

Today, the jaguar lives in fragmented areas half the total size of its historical range. Threatened by deforestation and other habitat loss from encroaching agriculture and infrastructure development, poaching, and other threats, the jaguar’s population is declining.

This is particularly acute in Mexico, where 6.4 million hectares – an area the size of the country of Latvia – of primary forest cover were lost between 1990-2015. In the country’s Central Pacific landscape, WWF is working with SIG’s support to restore and conserve key patches of the jaguar’s forest habitat. Informed by jaguar monitoring, WWF and local communities are collaboration to connect up these fragments through forest restoration and improved land management so that the jaguar can roam freely once again.

“Working with local communities that coexist with the jaguar, we are restoring 750 hectares of forest and effectively conserving 100,000 hectares of prime jaguar habitat,” said Sandra Petrone, Terrestrial Priority Species Coordinator, WWF-Mexico. After a comprehensive habitat analysis, the team have identified priority areas for reforestation and established local tree nurseries with hundreds of seedlings ready to start working their magic. Local communities have also been engaged on topics such as wildlife monitoring, improved livestock-management practices, and the reduction of human-wildlife conflict.

WWF-Mexico has been active in the Central Pacific landscape for over ten years, working on mangrove restoration and an innovative water management model, including establishing a water reserve to ensure this key resource is available for local communities and the environment. From 2022, the SIG support has allowed WWF to expand its engagement with local communities on topics such as wildlife monitoring, improved livestock-management practices, and the reduction of human-wildlife conflict.

The jaguar’s requirement of a large range, a healthy natural habitat, and an abundance of prey makes them a fantastic example of an umbrella species. To conservationists including WWF, this means that jaguar-focused conservation also helps protect all the other species in the same ecosystem, while benefiting local communities too. Just like an umbrella protects everything underneath it from the rain, the jaguar king can protect its kingdom and all who depend on it.

- Find out more about WWF’s project to conserve and restore the Central Pacific Corridor in Mexico: https://explorer.land/p/project/cpcmexico/about

- Find out about how WWF’s work with companies is supporting landscape conservation: https://forestsforward.panda.org/

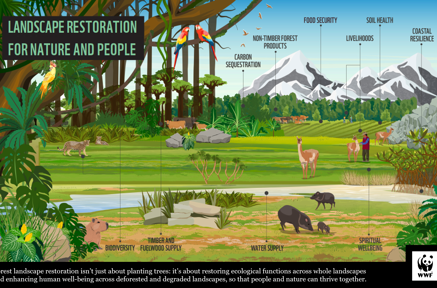

Beyond tree planting

Business is yet to unlock the true value of protecting and restoring nature